(In no particular order.)

Albireo

AlbireoA firm favourite among many amateur astronomers, Albireo (also known as beta-cygni) is actually a triple star system. Through a telescope though, it appears as a particularly beautiful visual binary -- a bright yellowish star with a fainter blue companion (shown here to the right). In 1976, astronomers at Kitt Peak discovered that the bright yellow star is actually a spectroscopic binary.

The two visual stars are around 380 light years away, and a huge 35 arcseconds apart. In other words, that fainter blue star (a fast rotating Be-class star) would take over 100,000 years to complete one orbit of the central binary -- assuming it's even part of the system.

Cygnus X-1

Cygnus X-1 is a very interesting little system. Discovered in 1964, it's one of the brightest x-ray sources in the sky, with a flux as high as 2.3x10-23 janskys (if you don't know what a jansky is, suffice to say that's surprisingly bright).

In fact, Cyg X-1 is one of the most promising candidates in the sky for a stellar mass black hole, with around 8.7 solar masses compressed into an estimated 26km event horizon. In a tight binary orbit (around 0.2AU) around the black hole, a blue supergiant orbits once every five and a half days in a nearly perfect circular orbit. It is slowly being ingested, as stellar material is drawn towards the black hole, forming an accretion disk. As the inner parts of this disk are heated to millions of kelvins, the atoms start to emit the bright x-rays as seen from Earth. Around 6000 light years away, there's a fair chance it could be part of the Cygnus OB3 association, which would make the system around 5 million years old. The black hole may have once been a star over 40 solar masses in size.

The evidence for Cyg X-1 being a black hole is actually so good that Stephen Hawking once lost a bet against Kip Thorne, acquiescing in 1990 that it could only be a gravitational singularity!

16 Cygni

70 light years away, 16 Cygni is a trinary system. A Sun-like yellow dwarf with a close(ish) red dwarf companion orbiting 73 AU away. Further out, another, slightly smaller, yellow dwarf orbits the main pair. Further out, but no one's entirely sure how far exactly, it would seem. Estimates range from 860 AU to 15,180 AU, giving an orbital period of anywhere between 18,200 to 1.3 million years. Another good example of how a tiny change in the calculations and observations can have a dramatic effect in astronomy. The 16 Cygni system is estimated at around 10 billion years old (so quite a bit older than The Sun), and has one known planet. Orbiting the smaller of the two yellow stars is a massive planet in a close elliptical orbit.

Interestingly, 16 Cygni is one of a select few stars which has had messages beamed to it via METI. If there's anyone there to hear it, they should receive it in November 2069. Who knows... With all the messages being send out, we might even have a reply sometime over the next 200 years or so.

Kelu-1

Quite nearby at only 30 light years away, Kelu-1 was only discovered recently. The reason why is simply -- it's a vanishingly faint brown dwarf system. Discovered in 1997, Kelu-1 was one of the first known free brown dwarfs not to be tied to a larger stellar companion. Since then, it's been visually confirmed that there are actually two visible brown dwarfs in the system.

In 2008 though, it was found that actually, it's probably a trinary system, with the "larger" of the two stars actually being a spectroscopic binary. The central pair, Kelu-1Aa and Kelu-1Ab are difficult to discern, but the orbiting dwarf Kelu-1B is around 6.5 AU from them, completing an orbit once every 38 years or so.

Pismis 24-1

Pismis 24-1In a stark contrast to the tiny Kelu-1 system, Pismis 24-1 is one of the heaviest trinary systems known. Interestingly, it's in very much the same configuration, with a spectroscopic binary pair too close to properly resolve, and another star at a somewhat greater distance.

It's part of the Pismis 24 open cluster -- a collection of some of the most massive stars known Pismis 24-1 is the brightest star visible in the picture to the left. Before it was discovered that this star is actually a multiple star system, it was estimated at nearly 300 solar masses. A single star simply cannot form with such a high mass -- it would be above the Eddington Limit. As you can imagine, this baffled a few astrophysicists for a while. All the same, three stars each weighing in at around 100 solar masses is still rather immense, but at least it's explainable by theories!

Castor

Located in the constellation of Gemini, Castor is a hexuple star system. In other words, it contains a whopping 6 stars! Visually, you can discern two separate stars, but each of them is also a spectroscopic binary. Both of these are actually an A-class star with a red dwarf companion. Another, fainter, companion star to the system is quite a rarity, in that it's an eclipsing binary system composed of two red dwarfs.

Quite a big family, as stars go.

40 Eridani

Just over 16 light years away, the 40 Eridani system is the home of the first white dwarf ever discovered. It's an interesting system because that white dwarf would once have been the main star observable. As a white dwarf, it's now little more than a stellar corpse, left orbiting the stars that were once its underlings. It now revolves in an eccentric orbit around 35AU from a red dwarf flare star companion. These two both orbit 40 Eri A, a red-orange dwarf star, roughly 400AU away.

There's a fair chance a habitable planet could exist in the 40 Eridani system. The habitable zone around the main star is around 0.6AU away (more or less the same orbit as Venus around the Sun). The other two stars would have little influence on such a planet, appearing as a bright red and white pair -- not bright enough to illuminate the planet at night, but bright enough to be visible during the day (assuming an Earth-like atmosphere). They'd appear as roughly magnitude -8 and -6 white and reddish stars in the sky. To compare, Venus is around magnitude -4.7 at its brightest.

Polaris

Polaris is surely amongst the most famous stars in the sky. 430 light years away, it's been used by sailors in the Northern hemisphere for hundreds (perhaps thousands) of years to navigate by. In fact, Polaris is actually another trinary system. The primary star in the system is a yellow bright giant. It's orbited closely by a hard-to-see dwarf star at around 18.5 AU, and more distantly by an F-class main sequence star, a huge 2400 AU away. The optimist in me would like to point out that an F-class star with solar metallicity could well be host to a habitable planet or two, though it's hard to say how safe it is being so close to a variable giant!

Polaris is another star which is farily popular among amateur observers. It's a classic population I cepheid variable (actually the closest one to Earth), and though I've never looked at it myself, I've heard others say that with a good enough telescope, you can even make it out as a visual binary.

TV Crateris

150 light years distant, TV Crateris (also known as HD 98800) is an interestting little quadruple star system. Firstly, all four stars are T Tauri stars (young stars, still not properly formed) and secondly, they all appear to be sun-like stars. Two close binary pairs orbit each other at around 50 AU, and as you'd expect from a young star system, there's a big dusty accretion disk surrounding the central pair.

Excitingly though, that disk isn't constant. It has a big clearing. Specifically, it's made up of an inner disk from 1.5 - 2 AU and an outer disk that starts around 5.9 AU. A big gap in a ring like that could quite possibly be caused by planets, either fully formed or still accreting material. Which is a logical assumption -- dusty disks are often associated with planets. It could well be that we're seeing planet formation happening in this system. If we are, they're going to be brightly lit planets for any life that might someday live there...

Alpha Centauri

Including Alpha Cen is almost obligatory in this list! A trinary system, I've written about it before at great length, as have many others. With good reason. Frankly, our nearest stellar neighbour, at a mere 4.37 light years away, is quite an inspiring place -- if for no other reason than that it's almost certainly going to be the first extrasolar system the human race eventually visits.

Appearing as a single star to the unaided eye, Alpha Centauri is the third brightest star in the sky. With a telescope though, it makes for a very pretty visual binary. Dim little Proxima, the third star in the system, appears about 2.2° away from the central pair. If it were bright enough to be seen by the naked eye, you wouldn't even think it was part of the same system.

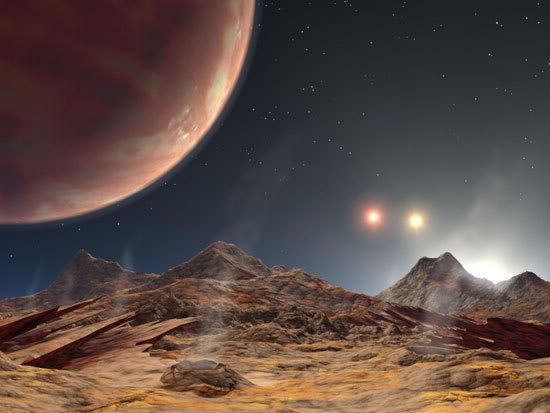

Standing on a rocky moon somewhere in the Alpha Centauri system might grant you a view a bit like this one...

Image credits (in order of appearance):

"Tatooine planet" - NASA JPL/Caltech

Albireo - Richard Yandrick

Pismis 24 open cluster - NASA, ESA and J. M. Apellániz

Alpha Centauri hypothetical planet - "The plague", Wikimedia Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment